Viruses Found to Use Intricate ‘Treadmill’ to Move Cargo across Bacterial Cells

State-of-the-art technologies reveal bacterial cells organized like human cells, offering insights for new phage therapies on untreatable infections

June 14, 2019

By Mario Aguilera

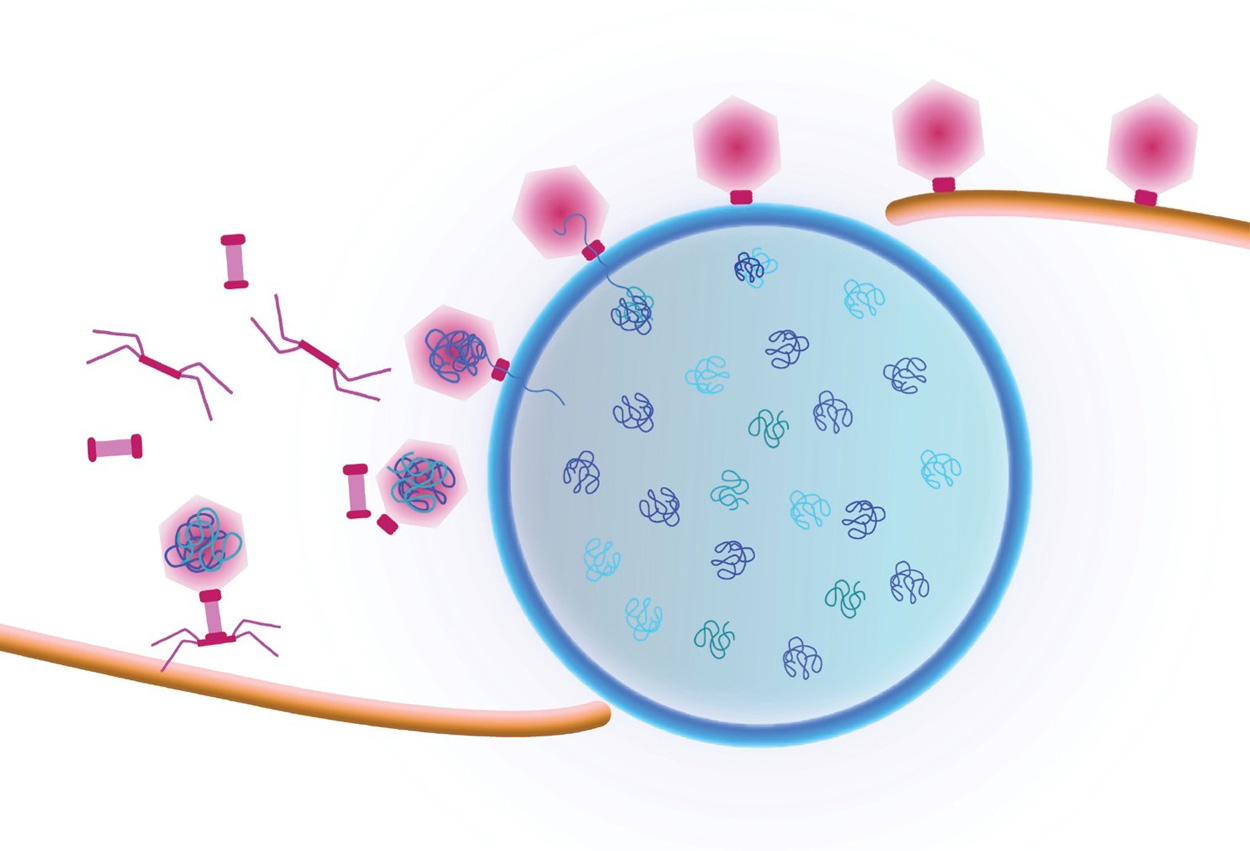

Cartoon showing a viral replication factory assembled by some jumbo viruses. Viral DNA replicates inside the nucleus (blue shell). Viral capsids travel to the nucleus along a treadmilling filament. Capsids dock on the nucleus in order to package viral DNA.

Pogliano/Villa Labs, UC San Diego

Countless textbooks have characterized bacteria as simple, disorganized blobs of molecules.

Now, using advanced technologies to explore the inner workings of bacteria in unprecedented detail, biologists at the University of California San Diego have discovered that in fact bacteria have more in common with sophisticated human cells than previously known.

Publishing their work June 13 in the journal Cell, UC San Diego researchers working in Professor Joe Pogliano’s and Assistant Professor Elizabeth Villa’s laboratories have provided the first example of cargo within bacterial cells transiting along treadmill-like structures in a process similar to that occurring in our own cells.

“It’s not that bacteria are boring, but previously we did not have a very good ability to look at them in detail,” said Assistant Professor Villa, one of the paper’s corresponding authors. “With new technologies we can start to understand the amazing inner life of bacteria and look at all of their very sophisticated organizational principles.”

Study first-author Vorrapon Chaikeeratisak of UC San Diego’s Division of Biological Sciences and his colleagues analyzed giant Pseudomonas bacteriophage (also known as phage, the term used to describe viruses that infect bacterial cells). Earlier insights from Pogliano’s and Villa’s labs found that phage convert the cells they have infected into mammalian-type cells with a centrally located nucleus-like structure, formed by a protein shell surrounding the replicated phage DNA. In the new study the researchers documented a previously unseen process that transports viral components called capsids to DNA at the central nucleus-like structure. They followed as capsids moved from an assembly site on the host membrane, trafficked upon a conveyer belt-like path made of filaments and ultimately arrived at their final phage DNA destination.

“They ride along a treadmill in order to get to where the DNA is housed inside the protein shell, and that’s critical for the life cycle of the phage,” said Pogliano, a professor in the Section of Molecular Biology. “No one has seen this intracellular cargo travelling along a filament in bacterial cells before.”

“The way this giant phage replicates inside bacteria is so fascinating,” said Chaikeeratisak. “There are a lot more questions to explore about the mechanisms that it uses to take over the bacterial host cell.”

Opening the door to the new discovery was a research combination of time-lapse fluorescence microscopy, which offered a broad perspective of movement within the cell, similar to a Google Earth map perspective of roadways, in coordination with cryo-electron tomography, which provided the ability to zoom into a “street level” view that allowed the scientists to analyze components on a scale of individual vehicles and people within them.

Villa said each technique’s perspective helped provide key answers but also brought new questions about the transportation and distribution mechanisms within bacterial cells. Kanika Khanna, a student member of both labs, is trained to use both technologies to gain data and insights from each.

“Zooming in and out allowed us to observe a unique example where things just don’t randomly diffuse inside bacterial cells,” said Khanna. “These phages have evolved a sophisticated and directed mechanism of transport using filaments to replicate inside their hosts that we could have not seen otherwise.”

Phage infect and attack many types of bacteria and are known to live naturally in soil, seawater and humans. Pogliano believes the new findings are important for understanding more about the evolutionary development of phage, which have been the subject of recent attention.

“Viruses like phage have been studied for 100 years but they are now receiving renewed interest because of the potential of using them for phage therapy,” said Pogliano.

The type of phage studied in the new paper is the kind that one day could be used in new treatments to cure a variety of infections.

Last year UC San Diego’s School of Medicine started the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH), which was launched to develop new treatments for infectious disease as widespread resistance to traditional antibiotics continues to grow.

“If we understand how phages operate inside bacteria and what they do, the end goal would be that you might be able to start designing tailor-made phages for particular infections that are resistant,” said Villa.

In addition to Chaikeeratisak, Khanna, Pogliano and Villa, coauthors of the study include Katrina Nguyen, Joseph Sugie, MacKennon Egan, Marcella Erb, Anastasia Vavilina and Kit Pogliano of UC San Diego’s Division of Biological Sciences; Poochit Nonejuie of Mahidol University in Thailand; and Eliza Nieweglowska and David Agard of UC San Francisco.

Funding for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (grants GM031627, R35GM118099, GM104556, GM129245, R01-GM57045 and 1DP2GM123494-01), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Thailand research fund and the Office of the Higher Education Commission (MRG6180027 and MRG6080081).