UC San Diego Biologists Discover Process That Neutralizes Tumors

Finding could bolster immune system's defense against invading cancer cells

July 10, 2018

By Mario Aguilera

The molecular "brake" known as PD-1 can bind and neutralize the same tumor cell, instead of an opposing tumor cell.

Researchers from the University of California San Diego have identified an unexpected mechanism that could help determine whether a cancer patient will respond to immunotherapy.

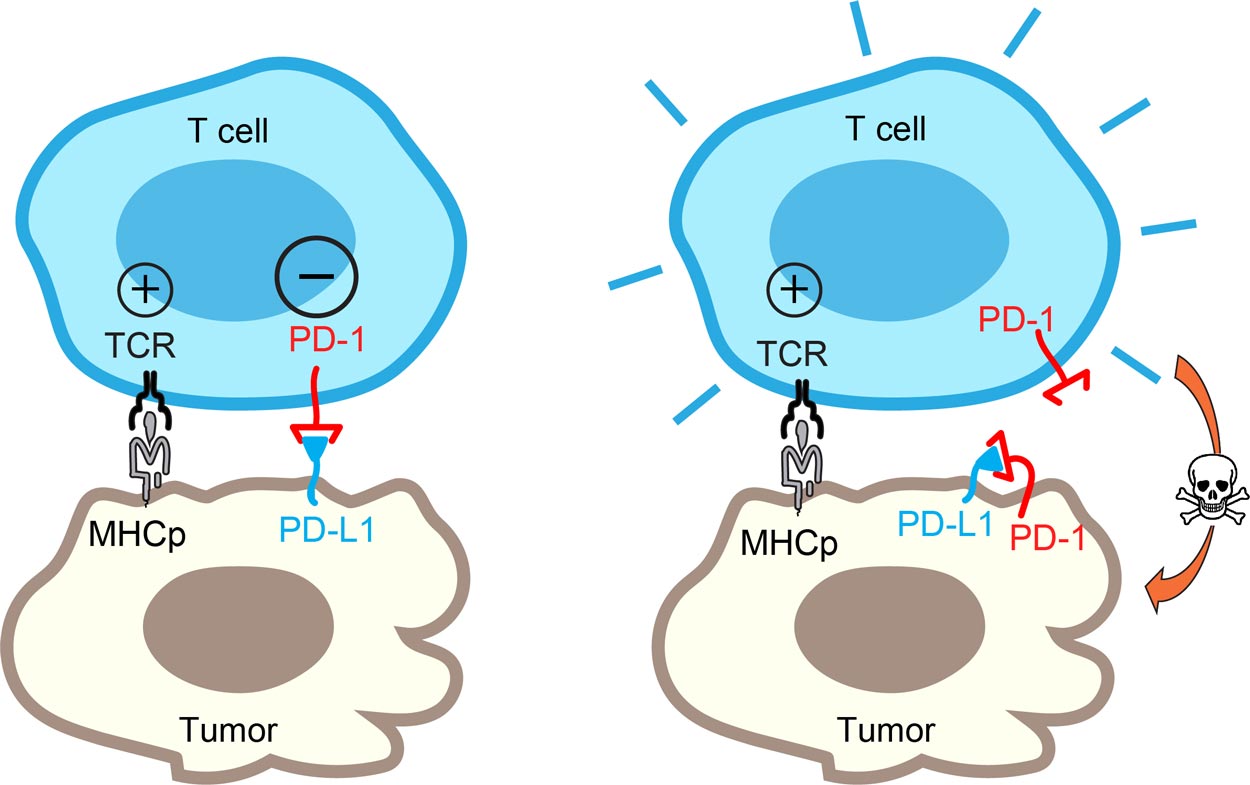

Ideally, the immune system identifies tumors as threatening elements and deploys immune cells (T cells) to find and kill them. However, tumor cells have evolved to employ a protein called PD-L1 to blind T cells from carrying out their functions and evade immune defenses. PD-L1 protects tumor cells by activating a "molecular brake" known as PD-1 to stop T cells.

In important therapeutic progress, antibodies developed to block PD-L1/PD-1 have been clinically proven to benefit certain cancer patients. Yet why some patients don't respond to such therapy has remained a mystery. Now, UC San Diego's Yunlong Zhao, Enfu Hui and their colleagues at the University of Chicago and the Nanjing Medical School in China have uncovered some clues.

As described July 10 in the journal Cell Reports, the researchers discovered an unexpected twist in the tumor versus T cell battle. Some tumor cells display not only their PD-L1 weapon, but also the PD-1 "brake." This simultaneous expression leads PD-1 to bind and neutralize PD-L1 on the same tumor cell. Thus, the PD-L1 on these tumor cells can no longer engage the PD-1 brake on T cells.

"It's a very exciting finding," said Hui. "Our study uncovered an unexpected role of PD-1 and another dimension of PD-1 regulation with important therapeutic implications."

This study suggests that patients with high levels of PD-1 on tumor cells may not respond well to the blocking antibodies because the PD-1 pathway is self-canceled. In these patients, mechanisms other than PD-L1/PD-1 are likely employed by the tumors to escape from immune destruction.

Looking to extend the immunotherapy potential of the finding, Hui and his colleagues are now seeking to determine additional mechanisms of "self-cancellation" at the interface of the tumor and immune cells.

"We think that our finding is the tip of the iceberg," said Hui, recently named a Pew Biomedical Scholar and Searle Scholar. "We speculate that self-cancellation is a general mechanism to regulate immune cell function. Understanding these processes more clearly will help develop better immunotherapy strategies and more reliably predict whether a patient will respond or not."

Coauthors of the paper, in addition to Zhao (a CRI Irvington Postdoctoral Fellow) and Hui, include Devin Harrison (supported by National Institutes of Health grant T32-EB009412) and Jun Huang (supported by NIH grants R00AI106941 and R21AI120010; and National Science Foundation CAREER award 1653782) from the University of Chicago, Yuran Song of UC San Diego and Jie Li of the Nanjing Medical School (China).

The research also was supported by UC San Diego startup funds to Hui.