Biologists Watch Speciation in a Laboratory Flask

November 28, 2016

By Kim McDonald

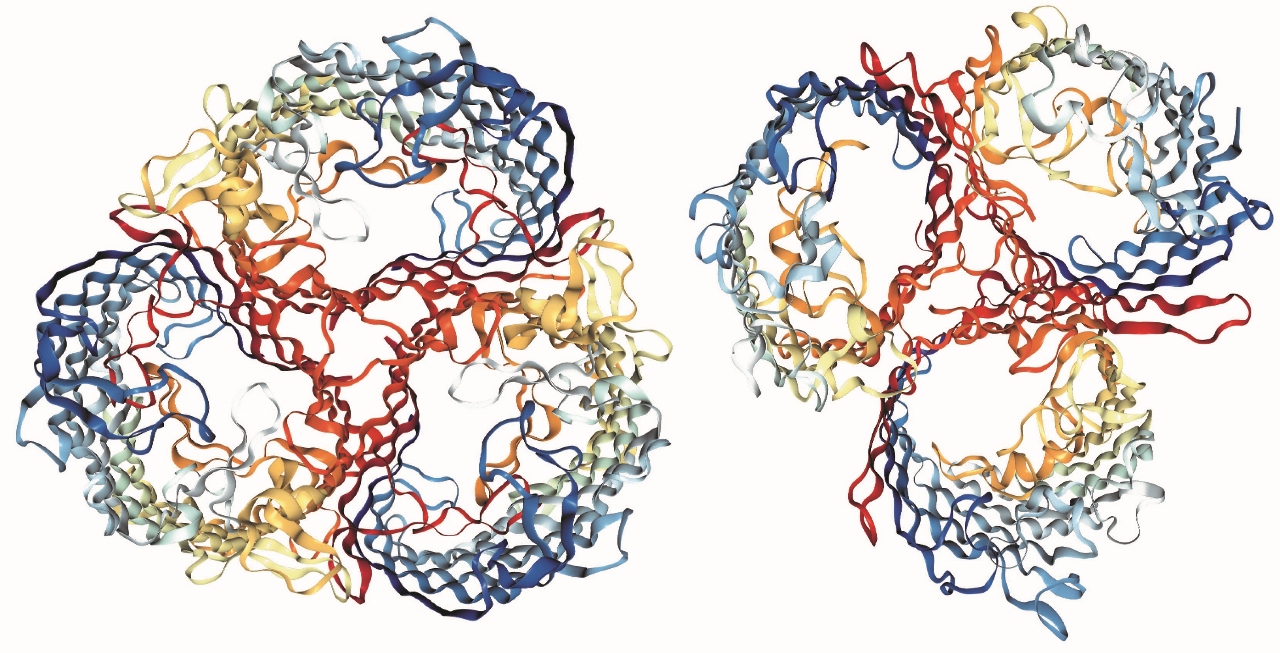

Molecular models of the two receptors the virus evolved to specialize on.

Justin Meyer, UC San Diego

Biologists have discovered that the evolution of a new species can occur rapidly enough for them to observe the process in a simple laboratory flask.

In a month-long experiment using a virus harmless to humans, biologists working at the University of California San Diego and at Michigan State University documented the evolution of a virus into two incipient species—a process known as speciation that Charles Darwin proposed to explain the branching in the tree of life, where one species splits into two distinct species during evolution.

“Many theories have been proposed to explain speciation, and they have been tested through analyzing the characteristics of fossils, genomes, and natural populations of plants and animals,” said Justin Meyer, an assistant professor of biology at UC San Diego and the first author of a study that will be published in the December 9 issue of Science. “However, speciation has been notoriously difficult to thoroughly investigate because it happens too slowly to directly observe. Without direct evidence for speciation, some people have doubted the importance of evolution and Darwin’s theory of natural selection.”

Meyer’s study, which also appeared last week in an early online edition of Science, began while he was a doctoral student at Michigan State University, working in the laboratory of Richard Lenski, a professor of microbial ecology there who pioneered the use of microorganisms to study the dynamics of long-term evolution.

“Even though we set out to study speciation in the lab, I was surprised it happened so fast,” said Lenski, a co-author of the study. “Yet the deeper Justin dug into things—from how the viruses infected different hosts to their DNA sequences—the stronger the evidence became that we really were seeing the early stages of speciation.”

“With these experiments, no one can doubt whether speciation occurs,” Meyer added. “More importantly, we now have an experimental system to test many previously untestable ideas about the process.”

To conduct their experiment, Meyer, Lenski and their colleagues cultured a virus—known as “bacteriophage lambda”—capable of infecting E. coli bacteria using two receptors, molecules on the outside of the cell wall that viruses use to attach themselves and then infect cells.

When the biologists supplied the virus with two types of cells that varied in their receptors, the virus evolved into two new species, one specialized on each receptor type.

“The virus we started the experiment with, the one with the nondiscriminatory appetite, went extinct. During the process of speciation, it was replaced by its more evolved descendants with a more refined palette,” explained Meyer.

Why did the new viruses take over?

“The answer is as simple as the old expression, ‘a jack of all trades is a master of none’,” explained Meyer. “The specialized viruses were much better at infecting through their preferred receptor and blocked their ‘jack of all trades’ ancestor from infecting cells and reproducing. The survival of the fittest led to the emergence of two new specialized viruses.”

Meyer’s study was conducted over six years in two separate labs. The first experiments were performed at Michigan State, supported in part by BEACON, the National Science Foundation’s Center for the Study of Evolution in Action, and the analyses were completed at UC San Diego.

Other co-authors of the study included MSU’s Devin Dobias, now a graduate student at Washington University; Sarah Medina, an undergraduate at UC San Diego, and Animesh Gupta and Lisa Servilio, UC San Diego graduate students working in Meyer’s laboratory.

UC San Diego News on the web at: http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu